What if the secret to getting unstuck isn’t making better plans, but running better experiments? Most of us approach life changes like we’re standing at the edge of a cliff—one massive leap that could end in triumph or disaster. But there’s a completely different way: treating your life like a laboratory where small, low-risk tests reveal what actually works for you. Whether you’re successful but restless, paralyzed by options, or simply curious about what else might be possible, the experimental mindset offers a practical framework for navigating uncertainty. It’s how I ended up moving from Los Angeles to Chicago, diversifying my investment strategy, and discovering that the biggest transformations don’t require knowing exactly where you’re going—they just require being willing to find out.

Table of Contents

- The Stuck Feeling We All Know

- How One Experiment Changed Everything

- Why Traditional Advice Fails

- Small Experiments, Big Changes

- A Simple Framework Anyone Can Use

- Professional Applications: From PM to Life Management

- The Power of Bias to Action

- When Procrastination Actually Helps

- Overcoming Mental Barriers

- Real-World Examples That Work

- Getting Started Today

- Key Concepts: Your Experimental Toolkit

Have you ever felt like you’re living the same week over and over again? Like you know things need to change, but you’re not sure what, how, or where to start?

Maybe you’re successful on paper but keep asking yourself “Is this it?” Maybe you’ve been doing the same thing for so long that you can’t imagine what else you’d even be good at. Maybe you want to try new things but can’t afford to fail—whether you’re surviving on cup noodles or have achieved FIRE status and are coasting on your riches.

Or perhaps you’re the type who researches everything to death, creating the perfect plan that you never actually execute. Maybe you know exactly what you want but feel paralyzed by all the ways it could go wrong. Maybe you’ve tried to make changes before, but they never stuck. (Some of us can barely plan what to have for lunch, let alone the next five years.)

If any of this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. And here’s what I’ve discovered: there’s a completely different approach to getting unstuck that doesn’t require massive changes, huge risks, or even knowing what you want. It’s called the experimental mindset, and it works whether you’re struggling to pay rent or wondering what to do with your investment portfolio.

The Stuck Feeling We All Know

Let’s be honest about what “stuck” actually feels like. It’s not dramatic—it’s subtle and frustrating.

Maybe you’re successful but keep asking yourself “Is this it?” Maybe you know things need to change but don’t know where to start. Maybe you’ve been doing the same thing for so long that you can’t imagine what else you’d even be good at. Or maybe you want to try new things but can’t afford to fail.

I see this everywhere. People working the same type of job for years, convinced they’re not qualified for anything else. Meanwhile, they effortlessly manage complex logistics in their personal lives that would challenge any project manager.

Or there’s the investment paralysis I used to experience. For years, I stuck with basic index funds through my M1 Finance setup because that’s what “smart money” does. It worked fine, but I was curious about real estate, individual stocks, even cryptocurrency. The problem? I couldn’t tell if my interest was genuine or just investment FOMO.

Here’s the thing about being stuck: it’s usually not about lacking options. It’s about not knowing which options are actually right for you. And the way most people try to figure that out—through endless research, pros-and-cons lists, or waiting for perfect clarity—often keeps them stuck longer.

How One Experiment Changed Everything

If you had told me at the beginning of 2024 that I’d be writing this post from Chicago, I would have laughed. Early last year, I was firmly planted in Los Angeles, working in the city and planning for retirement exactly where I was. Chicago wasn’t even on my radar.

But here’s what happened: instead of making a massive life decision, I approached it as an experiment.

The hypothesis was simple: “I think living in a different city might offer better quality of life and financial opportunities, but I’m not sure which city or whether I’d actually enjoy the change.” Rather than committing to a major move, I designed a series of small tests.

First, I spent a week in Chicago during winter (the worst possible time, by most accounts) to see if I could handle the climate. Then I researched the financial implications of relocating and tested out different neighborhoods virtually. I even experimented with remote work arrangements to see if my job could handle the transition.

Each small experiment provided data. The weather? Manageable with the right gear and mindset. The financial benefits? Significant enough to justify the move. The city itself? Absolutely wonderful in ways I hadn’t expected—the architecture, the food scene, the sense of community.

The beautiful part? I structured it knowing I could move back if needed. This wasn’t a permanent commitment—it was a one-year experiment with built-in flexibility. That reduced the psychological pressure and made the decision feel manageable rather than life-altering.

Now, sitting in my Chicago apartment, I realize this wasn’t just about changing cities. It was about proving to myself that I could navigate uncertainty systematically, make data-driven decisions, and adapt when new information became available. These are skills that apply to everything from career changes to investment strategies to daily life optimization.

Why Traditional Advice Fails

Most advice about making changes assumes you should already know what you want. “Follow your passion!” they say. “Create a five-year plan!” “Find your purpose!” But what if you don’t know what your passion is? What if your circumstances change? What if you’re just not a big-picture planner?

The traditional model is like trying to navigate a city you’ve never been to with a map from twenty years ago. It assumes the landscape hasn’t changed and that you know your destination.

There’s also something psychologists call “scarcity mindset” that makes change feel impossible. When you’re worried about money, time, or security, your brain literally can’t think as clearly about long-term possibilities. You get tunnel vision focused on immediate problems.

Research from Scarcity (Amazon link) shows that feeling resource-constrained actually reduces cognitive bandwidth—you temporarily lose 13-14 IQ points when you’re worried about money or time. No wonder big life changes feel overwhelming when you’re already stretched thin.

Then there’s what I call the “comparison trap.” We look at other people’s highlight reels and assume we should want what they have. But what works for someone else might be completely wrong for you. The experimental approach helps you figure out what actually works for your specific situation, personality, and constraints.

Small Experiments, Big Changes

Here’s a different way to think about change: instead of making big decisions, run small tests.

This idea comes from how scientists work. They don’t try to prove their entire theory at once—they design small experiments to test specific hypotheses. If the experiment provides useful data, they continue. If not, they adjust and try something else. The key insight? There’s no such thing as a failed experiment, only data.

Poker player Annie Duke makes this point brilliantly in Thinking in Bets (Amazon link). She explains that life is more like poker than chess—you’re always making decisions with incomplete information. The goal isn’t to be right every time; it’s to make decisions that give you the best odds of learning something useful.

This completely changes how you approach uncertainty. Instead of needing to know the outcome before you start, you design small tests to gather information. Instead of committing to major changes, you commit to learning experiments.

For example, when I was curious about real estate investing, I didn’t immediately buy a property or take an expensive course. I started with a tiny experiment: analyze one rental property listing every Saturday morning for a month, just to see if I found the process interesting. Cost: $0. Risk: minimal. Learning: significant.

By the end of the month, I knew I genuinely enjoyed the analysis process, understood my knowledge gaps, and had a realistic sense of whether this was worth pursuing further. That tiny experiment led to a systematic approach that’s become a meaningful part of my investment strategy.

Why Small Experiments Work

Small experiments work because they reduce psychological resistance. Your brain doesn’t see a 10-minute daily activity as threatening, but it will fight against “completely changing your life.” They also provide real data instead of hypothetical speculation.

A Simple Framework Anyone Can Use

The framework that’s made the biggest difference for me comes from Anne-Laure Le Cunff’s research in Tiny Experiments (Amazon link). She calls it PACT, and it’s simple enough to use whether you’re testing a career change or just trying to figure out if you’re actually a morning person (spoiler: you might not be, and that’s okay).

P – Purpose (What’s Your Hypothesis?)

Every experiment starts with a specific, testable hypothesis. Instead of “I want to be healthier,” try “I think taking a 10-minute walk after lunch will help me feel more energetic in the afternoon.”

The key is being specific about what you expect to learn. This makes it easier to recognize meaningful results when you see them.

A – Actionable (What Exactly Will You Do?)

Make the action so specific that there’s no daily decision-making required. “Exercise more” becomes “do 10 push-ups before my morning coffee.” “Learn about investing” becomes “read one financial article every Tuesday morning.”

This removes the mental load of constantly deciding what counts and what doesn’t.

C – Constrained (For How Long?)

Set a specific end date. Unlike habits that theoretically go on forever, experiments have clear timeframes. This removes the psychological pressure of permanent commitment.

For most experiments, 1-3 weeks is plenty. Long enough to see patterns, short enough to maintain motivation.

T – Trackable (How Will You Measure?)

Keep tracking simple. Often, a daily note about how you feel is sufficient. The goal is to notice patterns, not to create perfect data.

I learned this lesson from my investment tracking—sometimes the simplest metrics provide the most useful insights.

P: I think spending 15 minutes each morning planning my day will reduce my afternoon overwhelm

A: Write down three priorities before checking email or messages

C: Every weekday for two weeks

T: Rate my stress level at 3pm on a 1-10 scale

Professional Applications: From PM to Life Management

The experimental mindset isn’t just for personal decisions—it’s incredibly powerful in professional contexts. As someone who loves researching and acting on data, I’ve found that many principles from project management and business strategy apply beautifully to life design.

Agile Life Management

In project management, we’ve learned that rigid, long-term plans often fail because they can’t adapt to changing circumstances. Agile methodologies focus on short iterations, regular reviews, and responsive adjustments based on new information.

Your life can work the same way. Instead of five-year plans, try three-month experiments. Instead of annual reviews, do monthly check-ins on what’s working and what isn’t. Instead of betting everything on one big career move, test new skills or opportunities through side projects.

My Chicago move is a perfect example. I didn’t commit to relocating permanently—I structured it as a one-year sprint with regular retrospectives. Every quarter, I assess what’s working, what challenges have emerged, and what adjustments might improve the experience.

Risk Management Through Small Bets

In business, smart risk management involves diversifying your bets and limiting downside exposure while maintaining upside potential. The same principle applies to personal decisions.

Instead of quitting your job to start a business, test the business idea while employed. Instead of completely changing your investment strategy, allocate a small percentage to new approaches. Instead of moving across the country permanently, try a short-term relocation experiment.

This approach lets you gather real-world data while minimizing catastrophic risk. You’re not avoiding risk entirely—you’re being strategic about which risks are worth taking and how to structure them for maximum learning with acceptable downside.

Data-Driven Decision Making

I love researching and acting on data, and I wish more people would do the same. But here’s what I’ve learned: the best data often comes from your own experiments, not from endless research about what works for other people.

You can read every book about productivity, but only by testing different approaches will you discover what actually works for your brain, schedule, and lifestyle. You can study investment strategies all day, but only by making small, systematic tests will you understand your risk tolerance and find approaches that you’ll actually stick with.

This is why I track outcomes from my experiments systematically, just like I would track KPIs in a business project. The data guides my next experiments and helps me recognize patterns that wouldn’t be obvious otherwise.

The Power of Bias to Action

Amazon has a leadership principle called “Bias for Action” that I think about constantly: “Speed matters in business. Many decisions and actions are reversible and do not need extensive study. We value calculated risk taking.”

This principle can absolutely accelerate your personal life, but with an important caveat: not all decisions are reversible, and the key is learning to distinguish between reversible and irreversible decisions.

Two-Way vs. One-Way Doors

Jeff Bezos talks about two types of decisions: one-way doors (irreversible or very costly to reverse) and two-way doors (easily reversible). Most of our life decisions are actually two-way doors, but we treat them like one-way doors because we’re afraid of being wrong.

Moving to Chicago? Two-way door. I can always move back if it doesn’t work out.

Testing a new morning routine? Two-way door. I can return to my old routine anytime.

Trying a new investment strategy with 5% of my portfolio? Two-way door. I can easily adjust based on results.

Quitting your job without a plan? One-way door. Much harder to undo.

The experimental mindset helps you identify which decisions are actually reversible, then apply bias for action to the reversible ones while being more deliberate about the irreversible ones.

Speed as a Feature

Here’s something I’ve learned from both Amazon’s culture and my own experiments: speed of iteration is often more valuable than perfection of planning. The faster you can run small experiments, the more data you gather, and the better your decisions become.

This doesn’t mean being reckless—it means being systematically quick to test hypotheses that have limited downside. Instead of spending three months researching the perfect productivity system, spend one week each testing three different approaches. Instead of analyzing career options for a year, spend a month each informational interviewing in three different fields.

I’m not perfect at this—I still overthink some decisions and under-research others. But the experimental framework helps me recognize when I’m falling into analysis paralysis versus when I’m being appropriately thorough.

The Learning Velocity Advantage

When you bias toward action on reversible decisions, you increase your “learning velocity”—how quickly you gather real-world data about what works for you. This compounds over time, making you better at recognizing opportunities and avoiding pitfalls.

When Procrastination Actually Helps

Here’s something that changed how I think about procrastination: sometimes it’s not a character flaw—it’s valuable information.

When you keep putting something off, your brain might be trying to tell you something important. Maybe the task doesn’t align with your values. Maybe you don’t have the right resources. Maybe you’re doing it for the wrong reasons.

There’s a simple way to decode procrastination signals. I learned this from both Le Cunff’s work and Steven Pressfield’s insights in The War of Art (Amazon link) about internal resistance. (Yes, there’s actually a whole book about why you clean your entire house instead of doing the one important thing you planned to do.)

The Triple Check

Head: Does this make rational sense? Can you clearly explain why this task matters and how it connects to your goals?

Heart: Do you feel any genuine interest or positive emotion about this? Not every task needs to be fun, but persistent dread might signal misalignment.

Hand: Do you actually have the tools, skills, time, and resources needed to succeed?

If all three are solid but you’re still procrastinating, you might have external barriers that need addressing—like needing to have a difficult conversation or change your environment.

But often, one of these three reveals the real issue. I used this when I kept putting off learning about cryptocurrency. The Head part was questionable—I couldn’t clearly articulate why I needed to understand crypto beyond FOMO. That procrastination was actually protecting me from pursuing something for the wrong reasons.

On the other hand, when I procrastinated on tracking my expenses, the Head and Heart were solid, but the Hand revealed I needed a better system. That led me to try Monarch Money, which made the process simple enough that I actually stick with it.

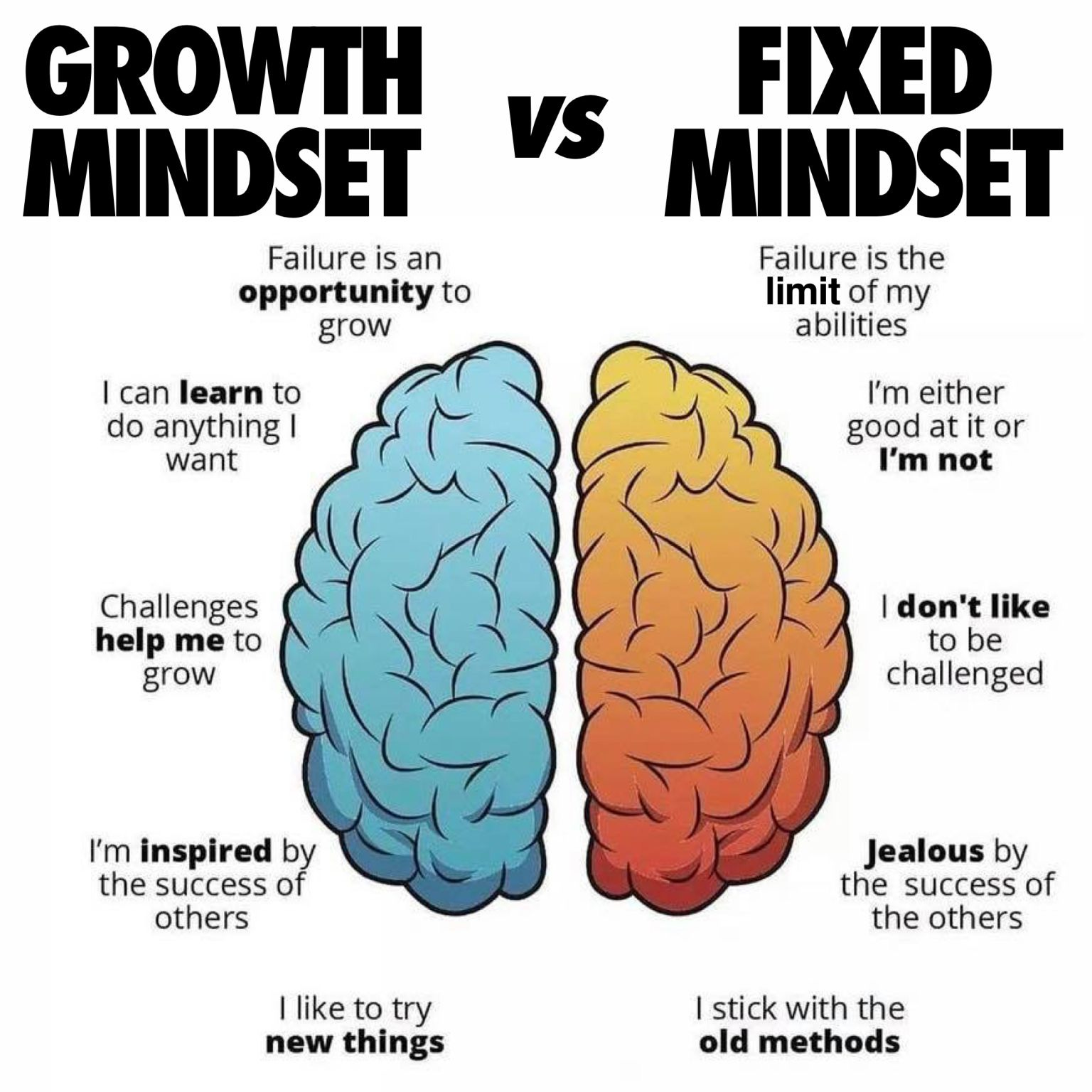

Overcoming Mental Barriers

Even with a good framework, our minds create obstacles. The biggest ones I’ve noticed in myself and others are what I call “mental scripts”—automatic ways of thinking that limit our options.

The “I’ve Always Been This Way” Script

This one sounds like: “I’m not a morning person,” “I’m bad with money,” or “I’m not creative.” These feel like facts, but they’re really just conclusions based on limited past experience.

One person I know ran this script for years: “I can only do administrative work.” But tiny experiments revealed she was actually great at training and mentoring—skills that opened up completely different career possibilities she’d never considered.

The “What Will People Think?” Script

This script makes decisions based on hypothetical judgment from others. The irony? Most people are too busy with their own lives to judge yours as much as you think.

I fell into this when I was interested in business credit cards for optimizing expenses. I worried it might seem “too intense” to friends who just use cash. But when I actually tested it with Chase Ink Business cards (links below!), I learned that most people were actually curious about the strategy.

The “All or Nothing” Script

This script says if you can’t do something perfectly or completely, why bother? It’s the enemy of experimentation because experiments are specifically designed to be small and imperfect.

Angela Duckworth’s research in Grit (Amazon link) shows that sustained progress comes from the combination of passion and perseverance—but that passion often develops through small experiences, not grand gestures.

Anne Lamott puts it perfectly in Bird by Bird (Amazon link): when a project feels overwhelming, focus on just one small piece. Write one paragraph, not a whole book. Try one small investment experiment, not a complete portfolio overhaul.

Reframing Obstacles

William Irvine’s The Stoic Challenge (Amazon link) offers a powerful reframe: treat every obstacle as a “challenge” designed to build your character. Failed experiments aren’t failures—they’re data that makes your next experiment better. It’s like turning life into a video game where every “failure” actually gives you XP points.

Real-World Examples That Work

Let me share some experiments that have worked for people with different constraints and goals:

Career Exploration (Low Cost, High Impact)

The Problem: Sarah felt stuck in accounting but had no idea what else she’d enjoy.

The Experiment: Every Friday afternoon for four weeks, she’d spend 30 minutes researching one job posting that seemed interesting, regardless of whether she was “qualified.”

The Learning: She discovered she was drawn to roles that involved training and developing others. This led to her transitioning into corporate learning and development—a field she’d never heard of before the experiment.

Financial Habits (Works on Any Budget)

The Problem: Mark knew he should budget but found every system overwhelming and restrictive.

The Experiment: For two weeks, he simply took a photo of every receipt and wrote down how the purchase made him feel (good, neutral, regretful).

The Learning: He noticed clear patterns about which purchases brought satisfaction versus which he regretted. This emotional awareness led to natural spending changes without restrictive budgeting.

Creative Exploration (The “Flow State” Test)

The Problem: Lisa felt creatively unfulfilled but didn’t think she was “artistic.”

The Experiment: Based on Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s research in Flow (Amazon link), she tracked her energy levels hourly for a week, noting when she felt most engaged and when time seemed to fly.

The Learning: Her flow moments happened when organizing information or explaining complex topics to others. This led her to start a blog and eventually freelance writing work.

Investment Strategy (Systematic Testing)

The Problem: I wanted to diversify beyond index funds but felt overwhelmed by options.

The Experiment: I allocated just 5% of my portfolio to test different asset classes one at a time through M1 Finance. First international ETFs, then REITs, then individual dividend stocks.

The Learning: I discovered I enjoyed researching individual companies more than I expected, and international diversification actually helped me sleep better during market volatility. This led to a more sophisticated but still manageable investment approach.

Professional Skill Development

The Problem: Tom wanted to transition into data analysis but wasn’t sure if he’d enjoy the day-to-day work.

The Experiment: He spent 20 minutes every morning for three weeks working through online Python tutorials before his regular job.

The Learning: He discovered he loved the problem-solving aspect but found pure coding tedious. This led him toward business analysis roles that use data insights without requiring heavy programming.

Getting Started Today

The hardest part about experimentation is simply starting. Here’s how to design your first experiment in the next five minutes:

Step 1: Pick Your Domain (1 minute)

Choose one area where you feel stuck or curious: work, money, health, relationships, creativity, or daily habits. Start with whatever feels most pressing or interesting.

Step 2: Create Your Hypothesis (2 minutes)

Complete this sentence: “I think [specific action] will [specific result] because [reason].”

Examples:

- “I think reading one article about career change every morning will help me feel less trapped because it will show me what options exist.”

- “I think taking a 5-minute walk between Zoom calls will improve my afternoon energy because I’ll get movement and fresh air.”

- “I think tracking my spending for one week will reduce my money anxiety because I’ll know where my money actually goes.”

Step 3: Design Your PACT (2 minutes)

Make it specific, simple, and short-term. If your first draft feels intimidating, make it smaller.

Common Starter Experiments

If you’re stuck choosing, here are some low-risk experiments that often provide valuable insights:

Ready-to-Use Experiments

- Energy Audit: Rate your energy level every few hours for one week to identify patterns

- Curiosity Log: Notice what you naturally research or read about for two weeks

- Morning Routine Test: Try the same 10-minute morning routine for 10 days

- Skill Sample: Spend 15 minutes daily for two weeks learning something you’re curious about

- Financial Awareness: Use Monarch Money to track spending for one month without changing anything

- Network Test: Reach out to one interesting person every Friday for four weeks

- Bias for Action Practice: For one week, make reversible decisions within 24 hours instead of deliberating

- Professional Experiment: Spend 30 minutes weekly for a month exploring one new skill or industry

What to Expect

Your first experiment probably won’t change your life dramatically. That’s the point. It will teach you something about yourself, prove that small changes are possible, and build confidence for bigger experiments.

The experimental mindset becomes self-reinforcing. Each small test makes you more comfortable with uncertainty and more skilled at designing useful experiments. Over time, this adds up to significant changes that feel natural rather than forced.

Most importantly, remember that there’s no such thing as a failed experiment—only experiments that teach you something unexpected. Sometimes the most valuable learning comes from discovering what you don’t want or what doesn’t work for your specific situation.

Key Concepts: Your Experimental Toolkit

Here are the core ideas we’ve covered, ready for you to reference and apply:

🧪 The Experimental Mindset

- Experiments vs. Plans: Instead of trying to predict the future, test your way toward it with small, low-risk experiments

- Data Over Drama: There are no failed experiments, only experiments that teach you something unexpected

- Process Over Outcome: Focus on what you learn about yourself, not just whether something “works”

- Speed of Learning: Fast iteration through small experiments beats slow perfection through endless planning

📋 The PACT Framework

- Purpose: Create a specific, testable hypothesis (“I think X will lead to Y because Z”)

- Actionable: Make the action so specific there’s no daily decision-making required

- Constrained: Set a clear end date (usually 1-3 weeks for most experiments)

- Trackable: Use simple metrics to notice patterns and insights

🔍 The Triple Check (Decoding Procrastination)

- Head: Does this make rational sense? Can you clearly explain why it matters?

- Heart: Do you feel any genuine interest or positive emotion about this?

- Hand: Do you have the actual tools, skills, time, and resources needed?

If all three check out but you’re still procrastinating, look for external barriers or systemic issues.

🚪 Two-Way vs. One-Way Doors

- Two-Way Doors: Easily reversible decisions where you can apply bias for action

- One-Way Doors: Irreversible or costly-to-reverse decisions that deserve more deliberation

- Most decisions are two-way doors but we treat them like one-way doors due to fear

- Professional Application: Use agile principles and regular retrospectives for life decisions

🧠 Mental Scripts to Question

- “I’ve Always Been This Way”: Past behavior doesn’t predict future potential—test new possibilities

- “What Will People Think?”: Most people are too busy with their own lives to judge yours as much as you think

- “All or Nothing”: Small, imperfect experiments often lead to bigger changes than waiting for perfect conditions

🚀 Getting Started Principles

- Start Smaller: If an experiment feels intimidating, make it smaller until it feels almost silly not to try

- Focus on Learning: The goal is to discover something about yourself, not to achieve a specific outcome

- Build Momentum: Success with small experiments creates confidence for bigger tests

- Reframe “Failure”: Unexpected results are often the most valuable—they reveal assumptions you didn’t know you had

- Apply Professional Skills: Use project management principles like risk management and iterative development

Your Personal Laboratory

The experimental approach to life isn’t about becoming a different person—it’s about systematically discovering who you already are underneath all the assumptions, fears, and limiting beliefs.

Whether you’re successful but sensing there’s more, feeling stuck in old patterns, afraid of making changes, or simply curious about what else might be possible—tiny experiments offer a way forward that works with your constraints, not against them.

The research from books like Switch (Amazon link) by Chip and Dan Heath, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Amazon link) by Daniel Kahneman, and Influence (Amazon link) by Robert Cialdini all points to the same conclusion: small, systematic changes compound over time into major transformations.

My Chicago experiment taught me that the most meaningful changes often come not from perfect planning, but from thoughtful testing combined with bias for action on reversible decisions. I love researching and acting on data, but I’ve learned that the most valuable data comes from your own experiments, not from endlessly studying what worked for other people.

I’m not perfect at this—I still overthink some decisions and under-research others. But the experimental framework has made me more comfortable with uncertainty, more skilled at recognizing which decisions deserve deep analysis versus quick action, and more confident in my ability to adapt when new information becomes available.

So here’s my challenge: design one tiny experiment today. Make it so small that it feels almost silly not to try. Run it for a week or two. Pay attention to what you learn about yourself, not just whether it “works.”

Because the goal isn’t to optimize your life into perfection—it’s to stay curious about what’s possible and build the skills to navigate uncertainty with confidence.

Your life is already an ongoing experiment—every choice you make provides data about what works and what doesn’t. The experimental mindset simply makes that process more intentional, systematic, and accelerated.

📚 Build Your Experimental Library

These books provide the research and frameworks behind everything we’ve discussed (Amazon links for easy ordering):

🧪 Foundation

- Tiny Experiments – The complete guide to life experimentation

- Thinking in Bets – Decision-making with incomplete information

- Mindset – The psychology of growth vs. fixed thinking

🛡️ Mental Tools

- The War of Art – Understanding internal resistance

- The Stoic Challenge – Reframing obstacles as growth

- Scarcity – How constraints affect decision-making

⚡ Peak Performance

- Grit – Building passion and perseverance

- Flow – Finding your optimal challenge zone

- Bird by Bird – Breaking big projects into small steps

🧠 Deeper Understanding

- Switch – The science of behavior change

- Thinking, Fast and Slow – How we really make decisions

- Influence – Understanding social pressure and personal choice

💰 Tools for Your Experiments

M1 Finance – Automate small portfolio experiments

Monarch Money – Track spending experiments

Chase Sapphire Preferred (link below!) – Earn rewards on learning experiences

Chase Ink Business (link below!) – Track entrepreneurial experiments

Using these links supports the blog and helps fund future experiments. Thank you!

🔗 Continue Experimenting

- Intrinsic Value of Stocks, Bonds, and Options – Apply systematic thinking to investment decisions

- Broke High Income Earner: A Guide to Financial Stability – Break cycles that keep achievers stuck

- Portfolio Analysis with Google Sheets – Systematic approaches to tracking what works

Trusted Tools & Services

I genuinely use these every day. If you sign up through these links, we both get a win.

Lifestyle & Ridesharing

Finance & Investing

M1 Finance

Get $75 when you sign up and fund a new investment account with $100 or more.

Robinhood

Get fractional shares worth $5-$200 when you sign up and link your bank.

Chase Sapphire Reserve® & Preferred®

Earn 125,000 points with Sapphire Reserve® or 75,000 bonus points with Sapphire Preferred®.

Chase Business Cards

Earn 200,000 bonus points with Sapphire Reserve for Business℠ or up to $1,000 cash back.

Venmo

Both you and your friend earn $5 when they make a qualifying payment of at least $5.

Webull

Join today and get up to 20 free stocks when you fund your account.

Coinbase & Coinbase One

Join Coinbase. Coinbase One members get $10 off next month per referral.

Monarch Money

My favorite tool for tracking all my finances in one place. Try it free for 30 days.

Kalshi

Trade on real-world events. Sign up and we both get $25.